Genocide .live

Confrontation during a solidarity protest against the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Silwan

Original Social Media Post

""Who pays to be here, traitor to the State of Israel?" Babes, if I was in it for money, I'd be on your side 📍Silwan, Jerusalem 🇵🇸" - Source

Tags

Event Notes

Eviction and ethnic cleaning in Silwan (East Jerusalem)Situation in 2019:

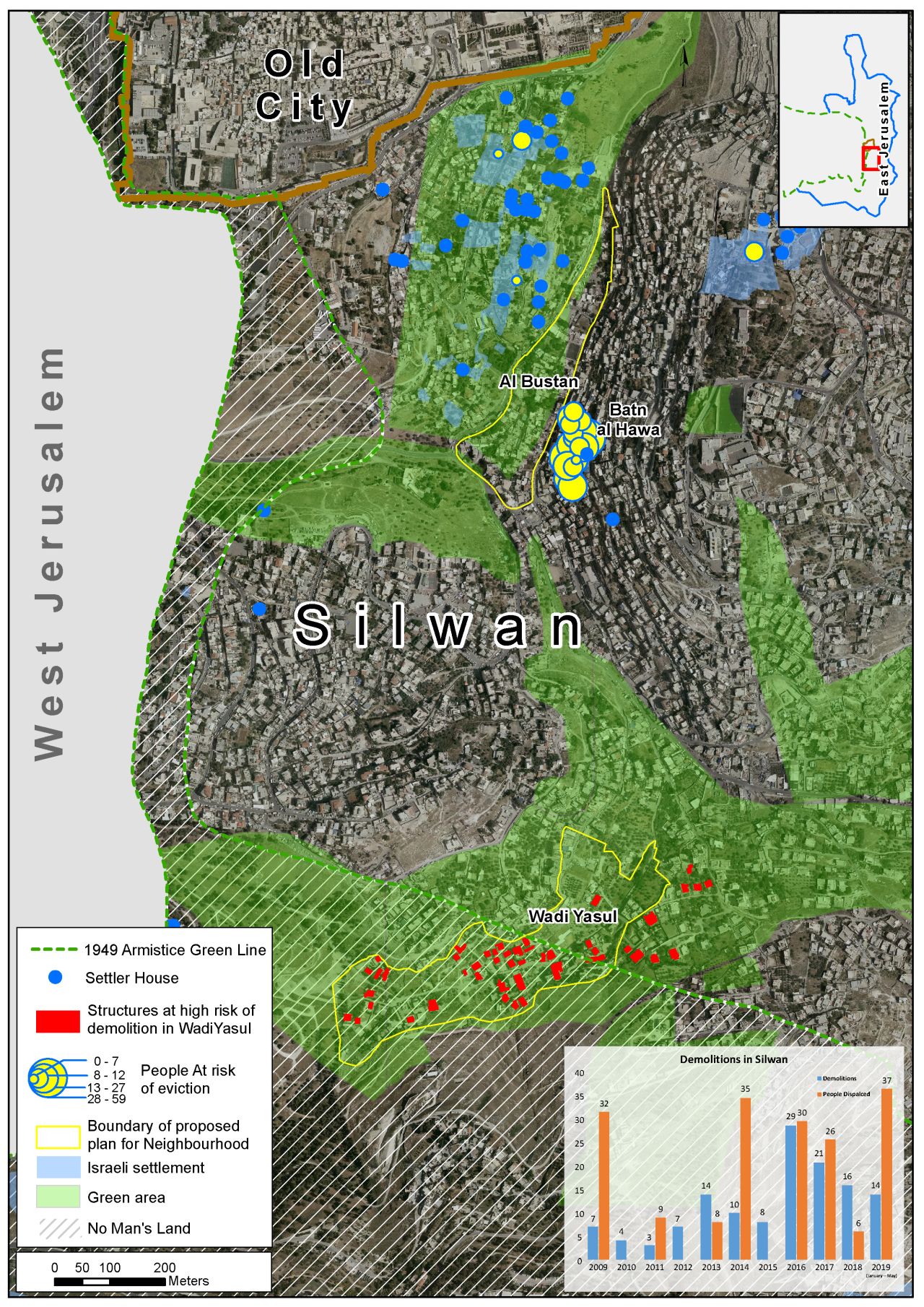

Silwan is a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem facing severe pressure from overcrowding, poor services, and widespread threats of home demolition and displacement due to restrictions on Palestinian construction. Areas such as al-Bustan have been designated as “green” or “open” zones where building is banned, despite long-standing Palestinian residence. Plans by the Jerusalem Municipality to build a tourist park in al-Bustan could result in the demolition of about 90 homes and the displacement of more than 1,000 residents.

Silwan is also a major target of Israeli settler organizations that take over Palestinian properties to establish settlement compounds. These takeovers often involve forced evictions, causing serious humanitarian impacts. The presence of settlements has created a coercive living environment for Palestinians, marked by heightened tensions, violence and arrests, movement restrictions—especially during Jewish holidays—and loss of privacy due to private security and surveillance.

Israeli settler organization Ateret Cohanim first turned to the courts in 2001, when three of its employees assumed control of the Benvenisti Trust — a fund established in 1899 to house Yemeni Jewish immigrants in Silwan, who later fled to other areas during the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-39 against British rule.

Although the trust ceased functioning long ago, Ateret Cohanim revived these ownership claims in 2002, positioning itself as the trust’s legal successor. In 2002, the state granted the trust ownership of 5.2 dunams of land in Batan Al-Hawa, and Ateret Cohanim immediately started filing lawsuits against dozens of Palestinian families living on these plots, despite never proving a connection to the original endowment. Through the trust, Ateret Cohanim subsequently gained control of an additional three dunams of land in the area.

Israeli courts support these claims by applying the 1970 Legal and Administrative Matters Law. This law allows Jews to reclaim property in East Jerusalem that was lost during the 1948 war, provided they can show prior ownership. Under this framework, settler groups can seek eviction orders even when Palestinian families have lived in the homes for generations and possess no alternative legal path to ownership recognition.

Critically, this law applies only to Jewish claimants. Palestinians who lost property in West Jerusalem or elsewhere in what became Israel in 1948 are barred from reclaiming their homes under the 1950 Absentee Property Law, which transferred their property to the Israeli state. As a result, the legal system permits restitution in one direction only.

In practice, this framework creates a one-sided legal mechanism: historical Jewish claims are recognized and enforced in East Jerusalem, while Palestinian claims from the same period are legally excluded. Human rights organizations argue that this imbalance enables settler organizations like Ateret Cohanim to use courts as tools for forced displacement and demographic change, rather than neutral adjudication of property disputes.

The municipality plans to establish an Israeli tourist attraction on the ruins of Al-Bustan—a move that would create territorial continuity between Israeli settlements in Silwan while further fragmenting and altering the Palestinian space in the area. What is unfolding in Al-Bustan is part of a state-led campaign to reshape the demographic and physical landscape of East Jerusalem through the displacement of Palestinian communities and the entrenchment of settler presence in Palestinian neighborhoods.

On June 23, 2025, Israel’s High Court of Justice ordered the eviction of the Al-Rajabi family from their home in the Batn al-Hawa area of Silwan, East Jerusalem, transferring the property to Israeli settlers. The ruling could displace around 30 family members and is part of a broader wave of legal cases targeting Palestinian residents near the Old City.

Silwan, home to about 60,000 Palestinians, has become a key target for settler organizations, particularly the group Elad, which—with government backing—has taken control of dozens of Palestinian properties in recent years. Local leaders warn that up to 87 families in Batn al-Hawa, totaling 700–800 people, face similar eviction threats.

Palestinian representatives and human rights organizations argue that Israeli courts are being used to legitimize settler expansion and forcibly displace Palestinians, describing the policy as discriminatory and aimed at changing Jerusalem’s demographic character.

On October 1, 2025, Peace Now reports (Eviction order until 10/19/25 for five families in Silwan for the benefit of settlers) that eviction orders were issued to Palestinian families in Batan al-Hawa, Silwan, including the Um Nasser Rajabi, Shweiki, and Odeh families, forcing them to vacate their homes or face police-enforced removal. The orders follow lawsuits by settlers linked to Ateret Cohanim, claiming historical Jewish ownership of the land.

Israeli courts, including the Supreme Court, rejected the families’ appeals, allowing the evictions. Peace Now highlights that these actions are part of a broader campaign affecting around 700 residents in 80 families, citing discriminatory laws that permit Jews to reclaim property lost in 1948 while denying Palestinians the same right.

In November 2025, Israeli authorities, backed by courts and the state, carried out evictions of Palestinian families in Batan al-Hawa, a densely populated area of Silwan just south of Al-Aqsa Mosque. Elderly residents, including Asmahan Shweikeh and Juma’a Odeh, were forcibly removed from lifelong homes, with police seizing properties and immediately transferring them to Israeli settlers linked to the settler organization Ateret Cohanim.

These evictions followed years of legal battles that culminated in Israeli Supreme Court rulings rejecting Palestinian appeals. In 2025 alone, nine Palestinian families in Batan al-Hawa were expelled, joining at least 16 others displaced since the early 2000s. Around 700 additional residents remain at risk, with eviction orders staggered to weaken collective resistance. The takeover of homes has transformed the neighborhood into a heavily militarized area marked by surveillance, private security, police raids, arrests, and settler violence.

Batan al-Hawa’s strategic location near the Old City has made it a central target in efforts to consolidate Israeli control around Al-Aqsa. Longstanding neglect of Palestinian services, combined with aggressive settlement expansion, has contributed to what residents and rights groups describe as the gradual erasure of Palestinian life from East Jerusalem.

On December 15, 2025, Israeli authorities forcibly evicted three Palestinian families from their homes in the Baten al-Hawa neighborhood of Silwan, south of Al-Aqsa Mosque in occupied East Jerusalem. The evictions were carried out in favor of the Israeli settler organization Ateret Cohanim and targeted the family of Um Nasser Rajabi and her sons, including relatives with severe medical and disability needs.

Officials say the evictions are part of an escalating campaign of displacement in Baten al-Hawa. Since June 2024, 13 homes have been evacuated, with dozens more at risk. Israeli courts are currently reviewing cases that could affect 26 homes housing about 250 Palestinians, and additional evictions are expected in early 2026.

Ateret Cohanim bases its claims on alleged Jewish ownership dating back to the late 19th century, using Israeli laws that allow Jewish restitution in East Jerusalem while denying Palestinians similar rights to reclaim property lost in 1948. Human rights groups argue this legal framework is discriminatory and enables mass evictions.

Baten al-Hawa’s strategic location near the Old City has made it a prime target for settler expansion aimed at consolidating Israeli control around Al-Aqsa Mosque. The eviction campaign is financially supported by U.S.-based, tax-deductible donations to Ateret Cohanim.

Palestinian officials and rights organizations describe the evictions as part of an ongoing system of forced displacement that violates international law and extends the historical dispossession of Palestinians into the present day.

On December 18, 2025: Israeli authorities issued evacuation orders to Jerusalem resident Khalil Basbous and his son Bilal, requiring them to leave their homes in the Batn al-Hawa neighbourhood of Silwan, south of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, by the fifth of next month. The orders were issued in favour of the settler organisation Ateret Cohanim, which claims the land as “Jewish-owned”. Eight members of the family, including children, live in the two homes.

In the same area, settlers, under the protection of Israeli forces, seized the homes of brothers Nasser and Aayed al-Rajbi and their mother. The settlers raised the Israeli flag over the houses after the family was forcibly evicted days earlier, also in favour of Ateret Cohanim.

On December 22, 2025, Israeli authorities demolished a four-storey residential building in the Silwan neighborhood of East Jerusalem, displacing more than 100 Palestinians from over ten families, including women, children, and elderly residents. Human rights groups described the operation as the largest demolition carried out in Jerusalem in 2025.

The demolition took place in the early hours of Monday under heavy police and security presence. Witnesses and AFP reporters said three bulldozers tore through the building as residents watched their belongings scattered in the street. Residents reported being awakened while asleep, given only minutes to change clothes and gather essential documents, and denied the opportunity to remove furniture. One resident, Eid Shawar, said his family of seven had nowhere to go and would be forced to sleep in their car.

Palestinian officials strongly condemned the demolition. The Jerusalem governorate, affiliated with the Palestinian Authority, described it as part of a systematic policy of forced displacement aimed at reducing the Palestinian presence in the city, calling it a war crime and a crime against humanity. Human rights organizations Ir Amim and Bimkom said the demolition was carried out without prior notice, just hours before a scheduled meeting intended to discuss possible legal solutions to prevent it.

Israeli authorities justified the demolition by claiming the building was constructed without a permit and was subject to a court-approved demolition order issued in 2014. The Jerusalem municipality said the land was zoned for recreational and sports use, not residential housing. Palestinian residents and rights groups reject this rationale, arguing that Israeli planning policies in East Jerusalem make permits nearly impossible for Palestinians to obtain and are used to deepen an already severe housing crisis.

On January 5, 2026, Israeli settlers seized the Basbous family home immediately after its evacuation in the Batn al-Hawa neighborhood of Silwan.

On February 5, 2026, The EU Representative, EU Member States and like-minded diplomatic missions (including Canada) visited Batan al-Hawa and Al Bustan in Silwan, East Jerusalem, amid an unprecedented surge in forced evictions, demolitions and settler takeovers of Palestinian homes.

On February 10, 2026, Israeli authorities and heavy security forces stormed the Palestinian neighborhood of Al-Bustan in Silwan, demolishing a commercial store and destroying walls of multiple Palestinian homes. Four Palestinians were injured while Israeli forces also arrested two young men after violently attacking them. This follows the recent distribution of 15 demolition orders in the same neighborhood, placing some 135 people at imminent risk of displacement.

The details for each video come from social media. None of it has been verified.